From the time he was young, Arthur was in and out of hospitals, visiting his father as he battled prostate cancer. “It brings back memories of times that weren’t so great,” he says. With his mother deceased and his father dying, Arthur began to bounce around from family member to family member across New Jersey, never quite finding a home. For a long time, those childhood memories persisted. “I was never really a fan of hospitals,” he says.

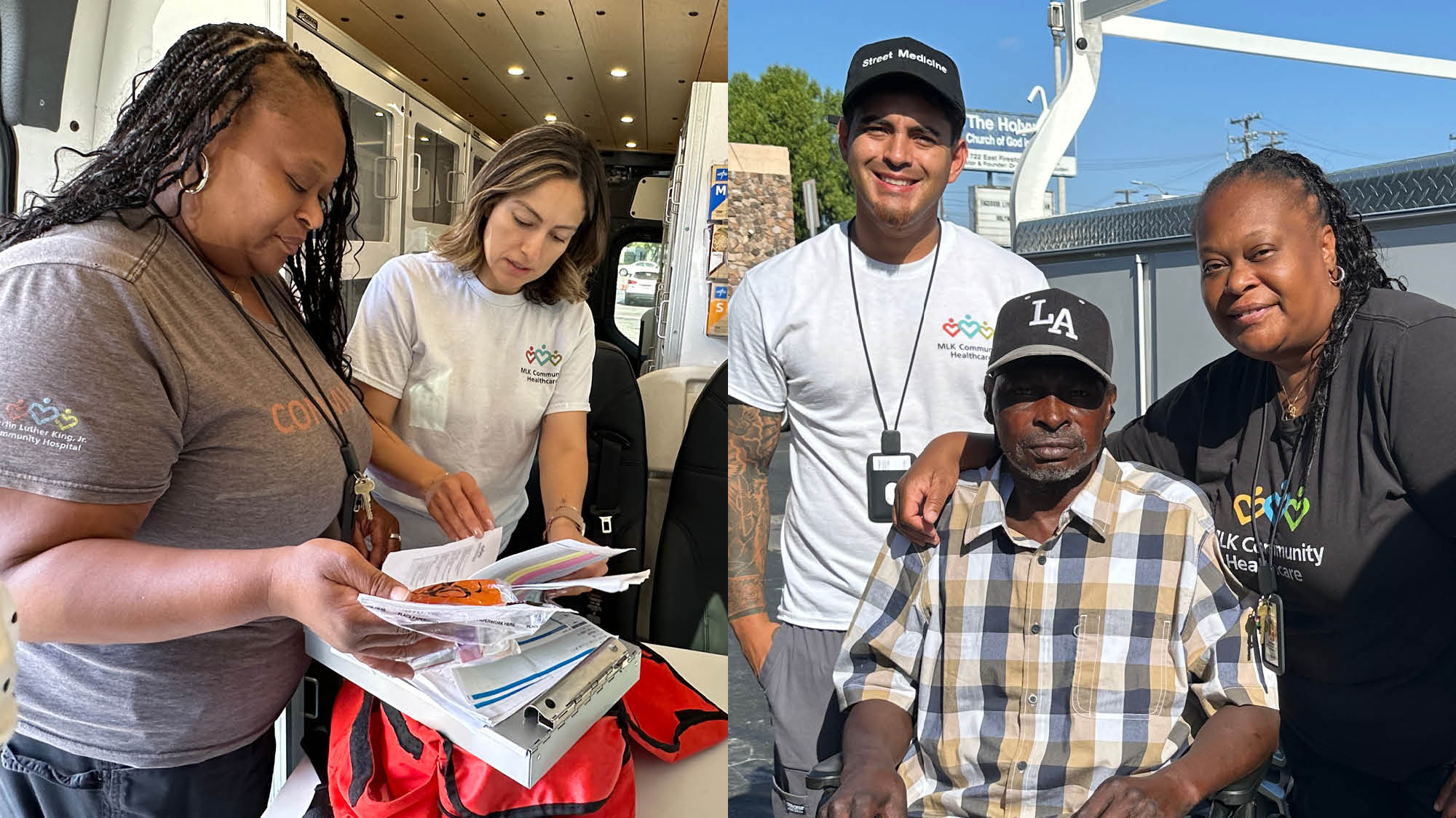

When Elsa, a nurse practitioner and team lead, and Beth, a nurse, first met Arthur two years ago, they had come to visit other patients living in the vacant lot at 86th and South Broadway as part of Street Medicine, a new department at MLKCH.

The idea of street medicine has been around for more than 20 years, but has gained increasing traction in just the last few years. Though programs vary in their approach, the basic goal remains the same: bring healthcare directly to unhoused patients, wherever they may be.

For those who often already distrust social systems, or have histories of abuse and trauma, entering a hospital or clinic setting can be a stressful experience. “Vulnerability takes on a different meaning for [these] patients,” says Dr. Sarat Varghese, Medical Director for Street Medicine and Hospital Medicine at MLKCH. “But if you look at in-home or concierge services in well-off areas, people do well because you serve them in their safe environment.”

In the last two years, California alone has gained more than 50 street medicine programs. MLKCH has gone one step further though—the health system has one of the first state-certified street medicine departments.

As a primary care team, Elsa, Beth, outreach coordinators Juan and Rodolfo, and the doctors not only treat patients where they are, but build relationships through follow-up visits every three weeks. The setup to see their approximately 400 patients is deceptively simple: A white truck packed with medical supplies, a folding table, a couple of stools. But from there, they’re able to provide a full range of care—medication drop-offs, wound cleaning, blood draws, whatever else a patient needs—all within feet of a patients’ tent or RV. If patients require more intensive care, the team can arrange transport to the hospital.

The need in South LA is clear—MLKCH serves an estimated 10,000 unhoused people each year throughout its health system. Living in the difficult and complex conditions of the streets, patients’ medical issues often go unresolved until they become life-threatening. Many whose needs are not critical have repeat visits to the emergency room for issues that could otherwise be managed with regular check-ups.

That was the case with Willie, a patient the team has now been visiting for the last six months. He can usually be found at Beach and Firestone Boulevards, cutting it up with friends. But before Street Medicine became his primary care team, Willie was struggling. He had severe pain and gangrene in his leg from an old bullet wound, and was often in and out of the emergency room. The leg required amputation, which MLKCH’s Dr. Myron Hall performed.

Since recovery, Willie has become a Street Medicine patient, receiving all his care without moving from his favorite block. The consistency has been vital to ensuring that his health remains stable. “They check on my feet, my legs, my blood pressure, my heart,” says Willie. “I know they’re gonna come, and when they come, I’m going to be here.”

As an adult, Arthur moved to Los Angeles temporarily to support his sister through a family tragedy. But he found he liked the city, and settled into a house on 87th Street in South LA. He’s held many jobs—telemarketing, selling industrial tools, working as a personal chef—but three years ago he lost his job, and with it, his ability to pay for housing. Out of options, Arthur began living in a tent in a vacant lot just a few blocks from his former home.

When Elsa and Beth first met Arthur two years ago, they had come to visit other patients in the area. Despite his dislike of hospitals, he immediately warmed to the team. “We laughed and joked a lot. Their street mentality is really good,” Arthur says. And, “They give these signs that they really, really care.”

Arthur became a Street Medicine patient without stepping foot into a hospital. The care that he receives goes beyond medicine. Street Medicine connected Arthur to MLKCH’s social workers and insurance navigators. They’ve helped him sign up for health and dental insurance, get into a work counseling program, and begin tackling the process of getting his legal documents back in order—paperwork that is often nearly impossible to maintain while living on the streets.

Now Arthur has been living in temporary housing at the motel for nearly two months, and is in good health. “They stayed on me. They’d say, ‘Take your medicine!’ And they didn’t give up.”

Both Elsa and Beth grew up in South LA and served in MLKCH’s Emergency Department before moving into Street Medicine. They’ve seen firsthand how great the need is in the community for quality healthcare—in an emergency room built to serve 35,000 patients a year, MLKCH’s sees 120,000 or more. For both of them, the work hits close to home. Attending to patients, “I see my uncles, I see my aunts, I see my cousins,” says Beth.

Demand for Street Medicine is growing, and MLKCH is building additional care teams and outfitting vans with funds raised by the Foundation to expand their reach. Dr. Varghese imagines a future with teams that can provide more specialized care—HIV management, hospice, women’s health, among others. One other unique aspect of the department: all medical residents at MLKCH are being trained to provide street medicine as part of their clinical practice, learning to consider unhoused patients’ contexts—such as how a lack of refrigeration may make taking certain medications impossible.

Measurable outcomes that prove the value of street medicine for a health system are emerging. Inpatient and emergency room readmissions for unhoused patients are down 14% since MLKCH launched Street Medicine two years ago. And patients are consistently meeting with their health team—a remarkable 99% show up for their scheduled visits.

For Elsa and Beth, there’s also something immeasurable in their work. Working so closely with patients, being invited into their tents and sitting at their tables, there’s an intimacy that creates a different dimension to the care. “We can relate to [our patients] knowing the struggles and dangers they’re facing,” says Beth. “We choose to have that connection to our patients,” says Elsa. “We end up loving them.”